Photo Story Exercise

In the spring of 2022, the Luis Alfaro Residency Project (LARP) launched “Speaking My Mind,” a series of storytelling and listening sessions. The community workshops—which were part of a larger series of events—drew from theatre making and storytelling to unpack issues around mental health. The sessions took place throughout various Chicago spaces, including the Pilsen Food Pantry’s community auditorium, the UIC medical hospital’s recently remodeled employee lounge, and the newly opened Gage Park Community Center. Participants included Chicago residents, medical professionals, youth groups, UIC medical students, social workers, health advocates, and community organizers, among others. Story-telling sessions were facilitated by renowned Chicano playwright and activist Luis Alfaro, with facilitation support from UIC collaborators; Dr. Young Kim in the classics department, Dr. Christine Dunford from the School of Theatre and Music (STM), Jacob Clinkscales, theatre major and student support staff, and me, a UIC Bridge Postdoctoral Research Associate in the STM.

When Dr. Dunford, fellow ethnographer and director of the STM, with years of experience in community-based work, and Dr. Kim, who previously worked as director of educational programs for the Onassis Foundation, approached me on joining the team, I was overjoyed. The LARP, specifically “Speaking My Mind,” was an exciting arts and mental health collaboration between university and community partners across Chicago. I felt the LARP—which was rooted in theatre and community building—aligned with my work as a theatre artist, scholar, educator, and community organizer. Before moving to Chicago in the fall of 2021, I spent a decade working professionally as a community arts organizer, activist, and supervisor of after-school arts programming throughout Southern California. As a community organizer, I was trained under John P. Kretzmann and John McKnight’s Asset Based Community Development model, and Relationship Based Community Organizing. I felt my strong background in group facilitation and community-based art (along with my work as a theatre maker) would be an additional asset to an already stellar team. I joined the group as a project director and helped conceptualize, design, and implement our vision for the workshops. I attended all but two sessions and participated in all community discussions. On one occasion, I even facilitated two community meetings, and would often help translate from English to Spanish throughout the workshops. We were all immersed in the facilitation of each session and supporting Alfaro’s lead, but more importantly, we were also deeply engaged as participants alongside the community.

Background on the Photo Story Exercise:

There was an undeniable sense that for many participants a conversation on mental health was long overdue. The story telling sessions were embraced as a gift that provided much reflection and comfort. People were so engaged in conversation (much credit to Alfaro’s facilitation style) that they continued sharing their stories long after the workshop had ended. On several cases, participants would return to the following week’s session where an entirely new group was expected. It was then that the facilitation team explored ways for participants to continue sharing well beyond the two-hour workshops, which is when the Photo Story Exercise was born. For this activity, participants were given one disposable camera (with capacity for twenty-eight exposures) and a series of prompts they would respond to using photography. These prompts were often used in the workshops during group discussions and as icebreakers. The submitted images would then be printed and shared on the project website. The three prompts created by Alfaro included:

- Take 3-5 pictures of Home: pictures of something that says ‘home’ to you

- Take 3-5 pictures of Neighborhood: pictures that are unique to your neighborhood

- Take 3-5 pictures of Love: pictures of things/people that you love.

Though we focused on the pandemic and its impact on mental health, including depression, anxiety, loneliness, and grief, Alfaro also encouraged us to consider ways we find strength and love in our work and communities. Participants were encouraged (though not required) to use the provided prompts in whatever ways they chose, or to incorporate new ones as they saw fit. Sixteen participants of the “Speaking My Mind” workshops comprised of community members, medical students, and health care professionals volunteered for the photo exercise. Shortly after the final workshop, I traveled throughout Chicago collecting cameras from participants to be developed at a local printer. Unfortunately, the camera labels were accidently erased during the printing process, therefor we cannot confirm what image responds to what prompt, nor who took what image. Thus, we will interpret these images as mostly anonymous submissions inspired by all, or none, of the prompts. In total, 265 photographs were submitted, which I then distilled to 169 viable photographs. Of the 169 photographs, I interpret thirty-eight images and feature at least one image from each participant. While only a handful of participants photographed the twenty-eight images, some photographed less than ten. The average number of images captured for this exercise was sixteen images. The images shown here represent all participants’ scope of ideas, without duplicating similar images. For example, some participants took several pictures of the same subject, in which case I would only use one of these images for the collage. After looking through all the submitted photographs, I discovered some unique patterns that I organized into three popular categories: pets, nature, and art/expression in public spaces. Except for one participant, everyone had at least one photograph under one, if not all, of these categories. Unlike other patterns not included in this analysis like architecture, people, or kitchen objects—the images presented here strongly reinforce participants’ stories shared in the workshops, specifically stories focused on mental health and healing. I found these images best suited in creating a themed collage because they reflected most participant submissions, highlighted some of the most uplifting conversations held during the workshop; were aesthetically pleasing, were fully developed and visible, or offered new insight into people’s relationships with mental health.

I chose collage making to engage with the visual data because collecting and compiling images to create a new image helps me understand visual patterns, themes, and ideas, and the process is quite therapeutic, which is fitting for this analysis. The featured collages are also a visual retelling of the stories shared throughout the workshops. Additionally, it was helpful to utilize only a small number of photographs from each participant to create a clearer, simpler, collage. Of course, many interpretations and patterns exist by viewing all the submitted images, including many not featured in this analysis; this is simply one version of many. On this webpage, you will find opportunities to view all the submitted images (unedited) that best speak to you. We invite you to identify new patterns for analysis and build a new collage. For my analysis, I investigate three patterns throughout the images—pets, nature, and art/expression in public spaces—centered on notions of healing. My analysis is led by the following questions: what were some discoveries made? What do these patterns say about participants in relationship to mental health in their lives and communities? In what ways are these photographs a continuation of conversations had during the “Speaking My Mind” sessions? What new information, if any, do they provide to the conversation?

Healing is Not Always with Medicine

Collage #1

Healing is Not Always with Medicine:

Participants Find Comfort in Caring for Others

The most photographed subject of all the submissions was the household dog. In total there were twenty-two images featuring participant’s furry family members. As a fellow dog lover, I found these images to be the most heartwarming of the entire selection. Participants photographed their beloved pets during walks, on their dog beds, peeking through the window, snuggling in blankets, next to their stuffed toy, and grinning at the camera. The photographs featured one Miniature Poodle, a Pit Bull, a Rottweiler, a Husky, and several smaller, mixed breed dogs. Unlike the other photographs I analyze, these sets include living creatures and the only subjects that are likely to have personal, emotional relationships with the photographers. Though, because of consent rights, we encouraged participants to refrain from taking photographs of people without written consent. And yet, there were still a handful of people photographed in several film rolls. Still, it is no surprise that if participants did incorporate prompts like “pictures of something that says ‘home’ to you” or “pictures of things/people that you love,” it would include images of beloved pets.

After looking through the photos, I recalled “Speaking My Mind” conversations centering participants and their animals, the power pets had in restoring and supporting their owner’s mental health. This was particularly common, as most participants experienced long bouts of social isolation during the beginning of Covid, which fueled people’s experience with depression and loneliness. It was often the case for participants (especially students) who lived alone or far from family, and/or were forced to work remotely from home. For several, the presence of a beloved animal became the only contact they had with a living being throughout the day. Pets were not only a distraction from the daily stresses of work and school, but they were also a source of comfort and refuge. Thus, family pets were a critical source of emotional and mental support during the pandemic.

Not only did household pets provide love and companionship during the pandemic, but pets also relied on their owners to reciprocate love, care, and affection. A participant once stated, “healing is not always with medicine,” referring to the therapeutic element in loving and taking care of another living creature. For people—especially those in the medical or social service fields— “healing” would also manifest through the selfless act of service for others, especially during the pandemic. Although folks were quick to share stories about the emotional and mental stresses in caring for patients and their communities, Alfaro encouraged us to also consider the joys in service to each other. The photographs of pets showcase the power of companionship and need for unconditional love during the pandemic, but also echoed conversations on our relationship to caring for others (animals and humans) as a restorative mechanism for all.

Smelling the Roses

Collage #2

Smelling the Roses:

Participants Refuel when Reconnecting with Nature

The second most popular subject submitted were images of nature. Half of the images were photographs of plants, bushes, and trees taken outdoors, while the other half featured house plants found indoors like the kitchen, living room or bedroom. Some of the plants were hanging from the ceiling near windows, inside a mason jar on a storage shelf, and inside vases on top of a dresser. The house plants were mostly green leaf plants, with a few others featuring beautiful reddish-purple leaves and in one case bright yellow flowers. The outdoor nature shots showcased a blossom tree, bright white and yellow flowers, as well as flower beds filled with blue, pink, yellow, red, purple, and white flower assortments. One can assume that these photographs would fall under any of the prompts be it images of participant’s home, neighborhood, or things they love.

It was evident (especially from participants in the medical or social service fields) that most people struggled to separate themselves from work related stress. One participant described this phenomenon as “taking one’s job back with you.” But in the spirit of healing, participants also shared ways they destressed from work or school to make room for joy and relaxation in their lives, like spending time outdoors and reconnecting with nature. It was also common that during the pandemic many participants took on new hobbies and projects, particularly during lockdown.

We can assume that these images reflect participants’ newfound connection or appreciation with their surrounding natural environments, a result of pandemic lockdowns or isolation. It could also be inspired by one of Alfaro’s discussions prompts in which he asked us to name our cross streets and aspects of our neighborhoods that inspired feelings of love and happiness. In both cases, these prompts encouraged us to consider our living environment, spaces, and neighborhoods as contributing factors to mental health and well-being. The submitted photographs of various natural elements embody participant’s association with home, neighborhood, or love. And in the spirit of selfcare, this prompt and exercise inspired participants to venture outdoors and truly “stop and smell the roses.” Despite the various geographics of participants throughout the sessions, every community represented offered something of healing and beauty.

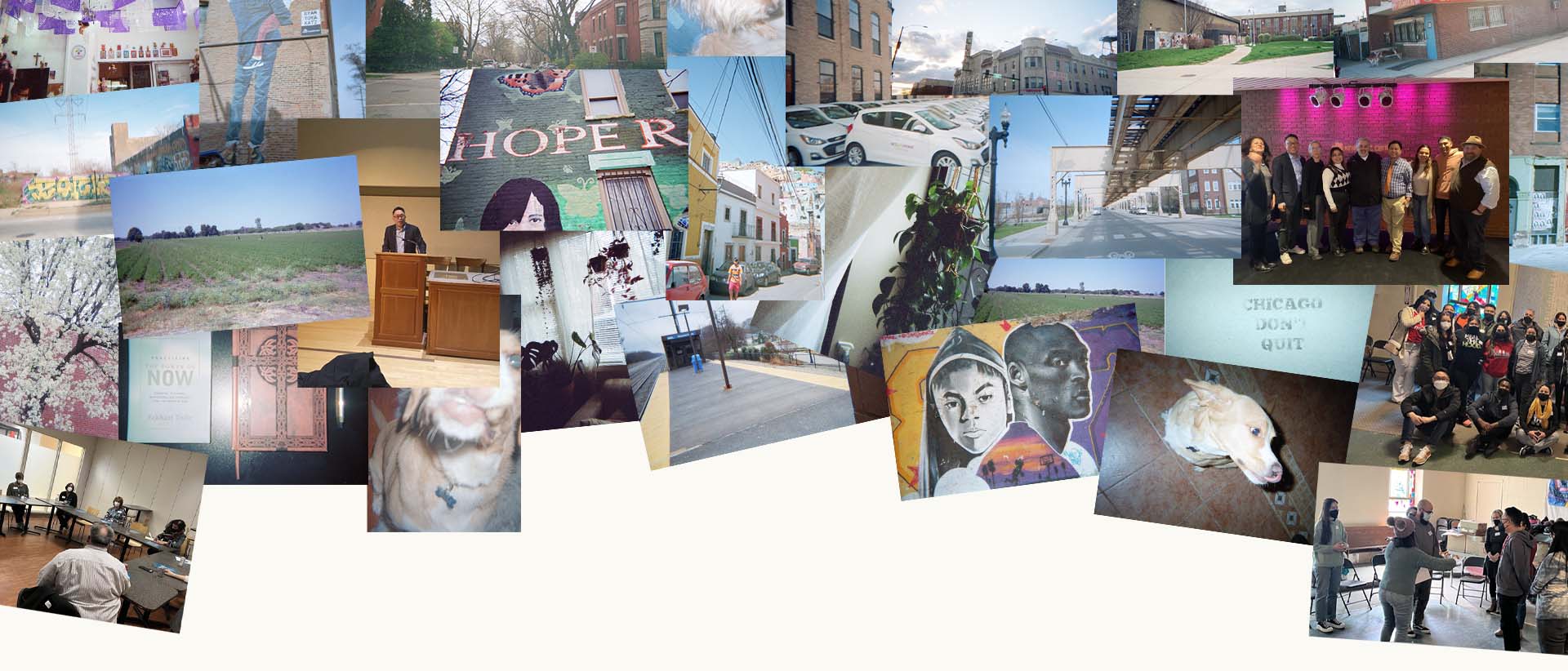

Chicago Don't Quit

Collage #3

Chicago Don’t Quit

Participants Draw Inspiration from

Public Art in their Neighborhoods

The third most common category was photographs of public art and visual messaging. These included snapshots of colorful murals on the sides of buildings, graffiti art on the walls of an underpass, and a window mural on a small business. The photographs also captured written messages, including a spray-painted stencil of “Chicago Don’t Quit” on a concrete background. Another photograph featured a sign on someone’s front porch with the words “Help Each Other” printed across in white letters. The last photograph with text includes “Fuck Real Estate,” spray painted in black paint on what seems to be a concrete wall or floor. I include both the painted subjects as well as the printed signs under public art.

It is likely that these photographs are a response to capturing something “unique to one’s neighborhood,” as well as the essence of one’s home. Either way, these photographs highlighted the use of public space as a means of public expression and the various ways our neighborhoods can be transformed into a canvas for art. We can determine that for participants including these works of public art as unique neighborhood qualities was a way of showcasing and celebrating its presence in their communities. Participants thus held these public art pieces as a sense of civic pride, the very essence of what they love in their neighborhoods. It was also evident in our story sessions that most of the participants had already experienced art as a mechanism for recovery and healing or were interested in engaging with the arts (in this case through storytelling and photography).

Participants captured several beautiful images of public art in public spaces, but some of the most moving images were those including messages, especially words like “Chicago Don’t Quit.” Now, we can’t be sure when the images where first displayed to the public, but what is certain is that reading those types of messages during a global pandemic carries extra weight. Participants captured these messages because they were either moved by them or because they agreed with the message. As a new resident of Chicago, I can testify to the undoubtful resilience held by Chicagoans during these difficult times. There were often several moments within our story telling groups when participants shared powerful stories of strength. It was inspiring to all, that in some way or another, we were all working through our own issues of mental health, but that in community one could find solace. As one participant declared, “In community everything is possible,” which referred to our various circles (professional or personal) and the roles these networks played in our mental health. These photographs, like the murals and signs urging us to help one another, captured both the creativity and the optimism of participant’s neighborhoods.

CONCLUSION:

The Photo Story Exercise offered participants an additional platform to discuss mental health, this time through visual imagery, inspired by notions of home, neighborhood, and love, and completely dictated by the photographer. The images, specifically the photographs of beloved pets, flowers, and nature, as well as public art and messages, proved there was much more to what were already rich conversations. For example, some of these photographs emphasized the themes of healing through care and compassion. Even in the state of global crisis and while dealing with their own grief and trauma, participants found solace in caring for each other. The overwhelming number of pet photographs also showcased participants’ need for companionship which aided in feelings of loneliness and isolation. The Photo Story Exercise gave us an additional glimpse into the personal lives of participants revealing various elements of love and beauty in their neighborhoods; a stark contrast to the darkness and tragedy brought on by the pandemic. Also, the images focused on flowers and nature showcased participant’s appreciation for their communities. Whether or not participants were taking time from their busy lives to step outdoors and “smell the roses” or if this photo project inspired them to take that leap is uncertain, but the exercise does demonstrate a connection between nature and mental health. As many participants shared, spending time outdoors in nature (meditating, walking, exercising, etc.) was a common approach to working through the stresses of a global pandemic. For many, it was the global lockdowns that forced, or inspired them, to reconnect with nature. Additionally, the Photo Story Exercise showcased the relationship between participants and public art or positive messaging in their neighborhoods. Similarly, the arts took on a new meaning for participants throughout the pandemic, whether it was a new appreciation for existing creativity in their communities, or truly seeing the work for the first time. Most, if not all, participants included art in their submission, revealing the universal language of the arts as a restorative mechanism in their lives.

Participants of the “Speaking My Mind” workshops discovered they all had experience in the art of storytelling, whether they realized it or not. Everyone has told a story at some point in the day. Under Alfaro’s encouraging guidance, participants used storytelling as creative expression in exploring serious issues like mental health. The stories shared throughout the “Speaking My Mind” sessions helped participants explore and unpack post-pandemic ideas, questions, fears, experiences, etc. The very act of storytelling can be a therapeutic experience itself and the Photo Story Exercise further contributed to those efforts because it provided a platform for participants to continue sharing experiences. Participants who submitted their cameras in person expressed their gratitude in exploring mental health on their own time through photography and found the experience, personal, enjoyable, and relaxing.

We are grateful to the following participants for giving us more insight into their relationships with mental health, this time through the lens of a disposable camera. We thank them for their insight and generosity. Please enjoy the full submission of unedited photographs through the link below.

We are grateful to the following participants for taking time to continue the discussions and giving us even more insight into their relationships with mental health and healing, this time through the lens of a disposable camera. We thank them for their insight and generosity. Please enjoy the full submission of unedited photographs through the link below.

Contributors to the project:

- Amy Bibiana

- Martin Finnegan

- Lizett C. Galan de Rosas

- Maria Gabriela Valle Coto

- Liset Garcia Peña

- Crystal Maciel

- Elisa Martinez

- Chioma Ndukwe

- Araceli Padron

- Aritha Parker

- Anna Paterson

- Michelle Sheena

- Ainsley Tran

- Plus, three anonymous participants